To celebrate women and girls in science, and inspire progress towards gender equality in STEM, the Royal Photographic Society's (RPS) Women in Photography Group launched their first annual Woman Science Photographer of the Year competition.

"Our culture cannot be imagined without science. And in our visual world, it’s not enough to just speak about science; we must also show it. For this, we need photographers to capture it and to share it."

Let's look at the two amazing winning images, and delve into the science behind them.

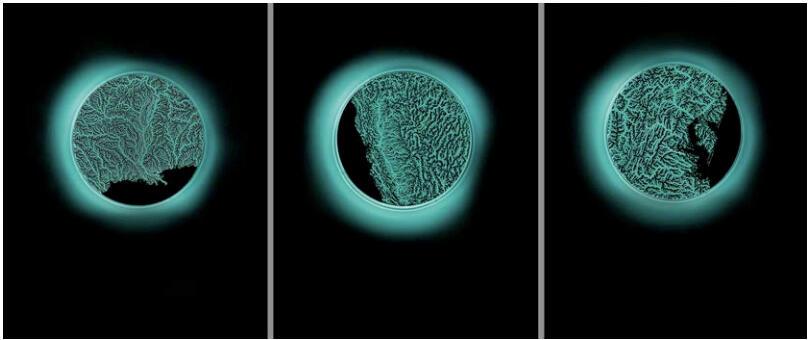

Overall winner - Margaret LeJeune

Margaret LeJeune is an image-maker, curator, and educator from Rochester, New York (USA). Her creative practice, which is anchored in photography, marries art, science, and technology. Her work focuses on the climate crisis including investigations of habitat loss, sea level rise, the current mass extinction event, and our precarious relationship with the natural world.

Her image "Watershed Triptych" harnesses the light of bioluminescent dinoflagellates to illuminate watershed maps from the United States Geological Survey Hydromap project. These organisms, colloquially known as sea sparkle, are also the same marine life that generate red tide algal blooms. Though sometimes naturally occurring, these harmful blooms have been increasing in numbers over the past 30 years as larger and more powerful storms flood factory farms causing excessive nutrients to spill into the waterways from CAFO overflows. These maps represent the three largest watersheds in the United States and the outflow areas where algal blooms have been recorded.

How bioluminescence works - with Peter Gallivan (Zoologist and Ri Family Programme Manager)

The ethereal blue glow seen in these algae is actually created a chemical reaction, in a process called bioluminescence. During this reaction, a molecule called luciferin is broken down and combined with oxygen, or oxidised. This reaction gives off light – the exact colour of this light depends on the shape of the luciferin molecule, which can vary between organisms.

This light is visible because the reaction is sped up, or catalysed by a molecule called luciferase. This luciferase molecule has a similar structure to the chlorophyll molecule used by plants and algae in photosynthesis, suggesting this to be it’s evolutionary origin. This reaction is actually a defence mechanism in these algae, and is usually triggered when they are disturbed or jostled, most often simply by a breaking wave.

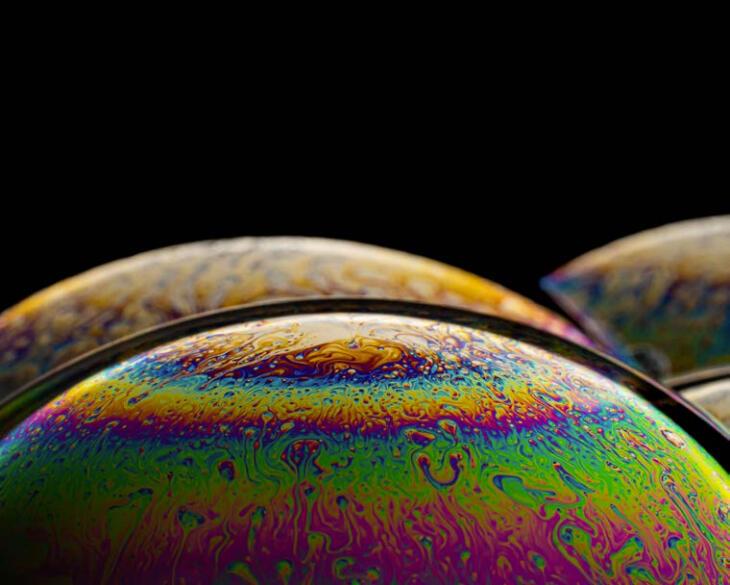

Young photographer winner - Kelly Zhang

Kelly Zhang is a young photographer based in New York, USA, specialising in abstract macro photography. Currently, she is a junior at Jericho High School in Long Island. Inspired by the scientific phenomena behind soap bubbles, Kelly began photographing them in 2022. The swirling pattern of iridescent colours in the bubbles, caused by thin-film interference, symbolises the transitory nature of our lives.

The science of bubbles

The reason we see those beautiful colours on the surface of soap bubbles is due to a phenomenon called iridescence. In a bubble film, there’s a layer of water trapped between two layers of soap. When light acts as a wave and reflects off the two soapy films, they interact and interfere in different waves so that some parts are cancelled out, and others are amplified.

The thickness of these three layers of soap and water will vary across the bubble's surface, creating colourful iridescence patterns.

But why do bubbles form in the first place? Soap molecules have two ends: one that is attracted to water (hydrophilic) and one that tends to avoid water (hydrophobic). The hydrophobic parts gather at the surface, and stick out in order to avoid the layer of water, separating the water molecules from each other in the process.

This distance decreases the surface tension, allowing bubbles to form.

Soap bubbles have fascinated scientists for centuries. James Dewar (inventor of the Dewar flask, aka the Thermos) kept a bubble in a jar for five weeks, which became the talk of the town and received press coverage on whether it burst every day.

If you can’t get enough of gorgeous iridescence patterns, check out this early 1930s film from our archives.

About the competition

This is the first annual edition of the Royal Photographic Society's Woman Photographer of the Year Award, shining a light on women's contributions to research and innovation. Find out more about RPS Women in Photography

Explore more science

Every week at the Ri you can experience science in action through inspiring talks from the world's top experts in physics, chemistry, engineering, mathematics and more. You can join us in person in the heart of London, or via livestream from anywhere in the world.