We’re all familiar with the trappings of science fiction, many of which generously stretch the possibilities of real science. But the genre is not just a place for outlandish escapism: it holds an important position in contemporary culture, and its influence can even be seen in the direction of some real scientific and technological advances.

Science fiction on screen is immensely popular: of the current top five grossing films of all time, only Titanic is outside this genre. It’s also central to the history of film: the move to narrative filmmaking, which defined cinema as we know it today, is widely associated with the work of Georges Méliès around the turn of the 20th century. An illusionist who saw the potential of film for creating special effects, Méliès experimented with this new technology through a series of fantastical tales.

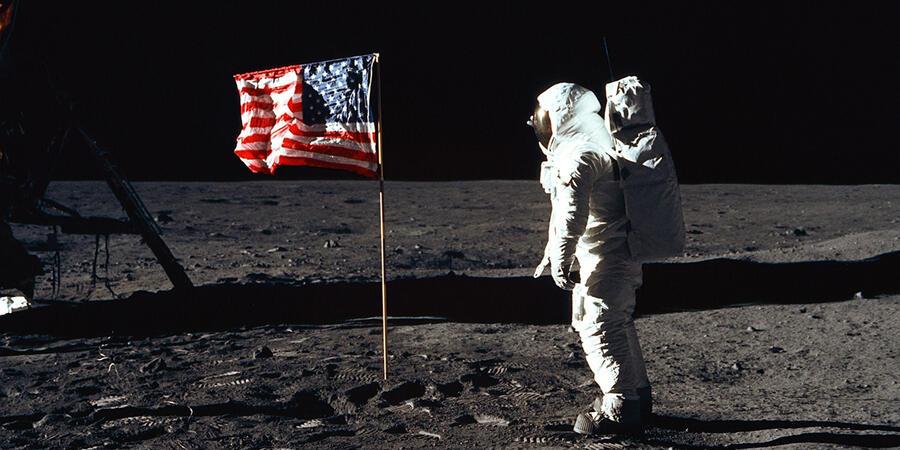

His most influential film, A Trip to the Moon, depicts a group of astronomers travelling to the Moon, exploring its surface, battling its inhabitants and returning to Earth – all within 15 minutes. This short film pushed the boundaries of what was possible for the medium and shaped the future of cinema. It's also an excellent example of scientific achievements first being imagined in the realm of fiction: A Trip to the Moon came out in 1902, 67 years before Neil Armstrong took one giant leap for mankind.

Science fiction often serves as an inspiration for real scientific research and developments. Sometimes, the language of fiction shapes our thinking and approach to scientific investigation. Professor Richard Ellis, a leading astronomer who will be sharing his discoveries in modern cosmology as part of our public programme of talks this spring, notes:

"One of the most exciting aspects of exploring outer space is our ability, using large astronomical telescopes, to peer back in time. Time travel has been a staple of science fiction for over a century but, due to the finite speed of light, astronomers are unique in being able to witness the universe in its past."

But the connection between science fiction and science fact isn’t always metaphorical. Although not as extraordinary as visiting the Moon, many now-common gadgets were imagined in science fiction before entering the real world. The classic series Star Trek features several everyday technologies that seemed far-fetched in the ‘60s: video calls, automatic sliding doors and flip phones. These last are already becoming a thing of the past, but the rise of foldable smart phones evokes the folding screens found in other popular science fiction stories such as Minority Report or Westworld.

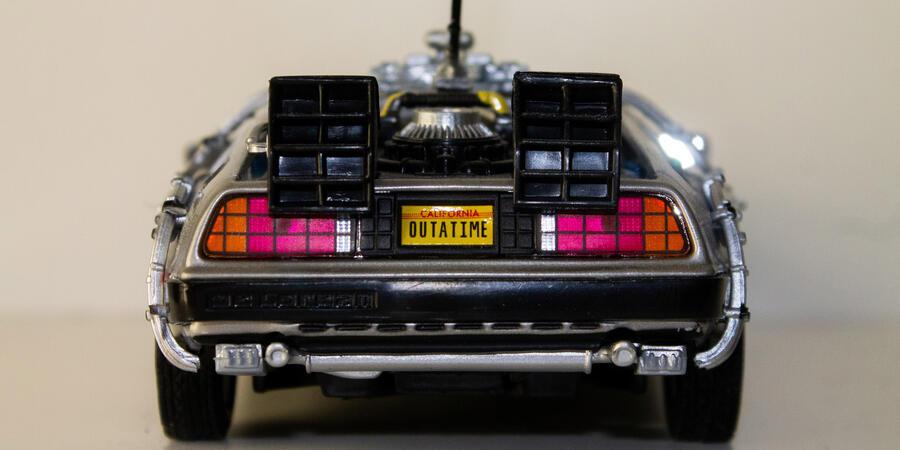

And it’s not only generalised visions of the future that find their way into reality: certain gadgets have been specifically designed to replicate fictional tech. In 2016, Nike produced a limited run of self-lacing shoes modelled after those featured in 1989’s Back to the Future Part II. This product wasn’t just a fun gimmick: Nike partnered with Michael J. Fox, who played Marty McFly in the Back to the Future trilogy, to raise money for his foundation to fight Parkinson’s.

The influence of particular works of science fiction extends beyond the realm of technology and can even shape scientific investigations. Take, for example, the black hole simulation developed for Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. To create the images seen in the film, Nolan asked Paul Franklin, the film’s visual effects supervisor, to work with Interstellar’s Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physics consultant, Kip Thorne. This was no small task for either of them. Thorne provided pages of detailed equations while Franklin and his team had to code new software to render the image, as the options they had available at the time worked on the (usually reasonable) assumption that light travels in straight lines.

The resulting simulation provided new insights on gravitational lensing around black holes which Thorne and Franklin, along with co-authors Oliver James and Eugénie von Tunzelmann, published in two technical papers after the film’s release. The requirements of science fiction shaped the direction taken by a leading physicist in his own work. And the simulation remained in discussion long after the film’s release; comparisons were drawn in 2019 when the first real-life images of a black hole were captured – images which Dr Ziri Younsi, who was involved in this endeavour, will explain here at the Ri later this year.

So, the influence of onscreen science fiction is not reserved for box-office takings, but can inspire real change in science and society. We can only wonder what fantastic inventions may emerge from the screen in future years – and hope that they continue to provide positive development and do not send us in to the dystopian side of science fiction.

Explore science

Dive into our public programme of science talks to expand your knowledge of all things science, from physics to biology.

About the author

Megan Stephens is an AHRC-funded PhD student researching representations of death in contemporary media. She has recently completed a three-month internship with us, applying her research skills to the archives and history.