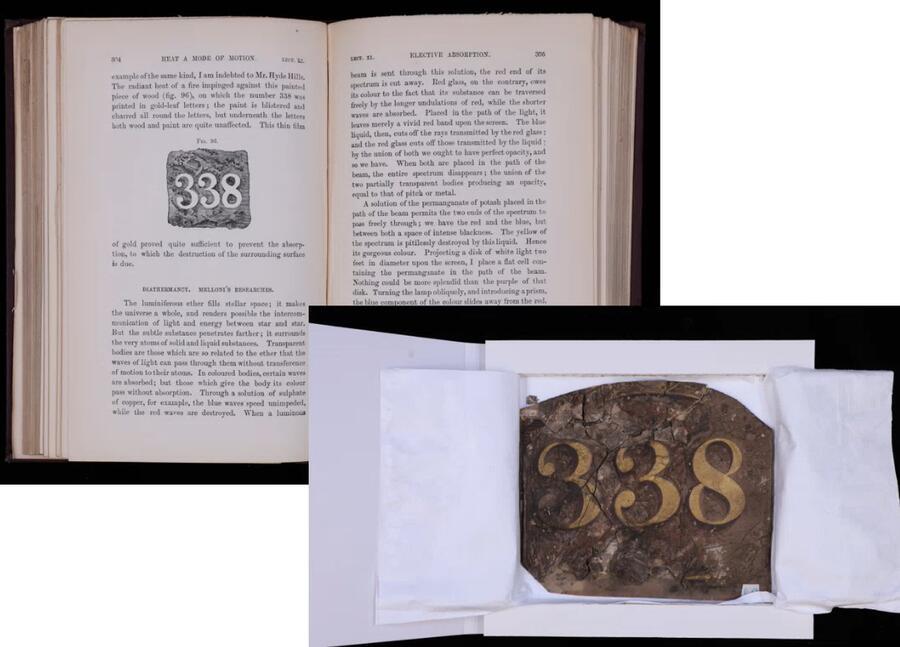

The archives of the Ri are home to many fascinating pieces of scientific history, some of which are still used to demonstrate experiments to this day. One such example is a piece of burnt wood, which John Tyndall, the Ri’s Professor of Natural Philosophy 1853-1887, used in a Friday Evening Discourse experiment in 1862. It was also featured in Tyndall’s publication Heat. A mode of motion.

While this burnt piece of wood is unique simply for being part of a ground-breaking experiment showing that gold-leaf was sufficient to prevent the absorption of heat by the wood, it was also intriguing that the numbers 338 were chosen to be printed on it. The publication made no mention of whether 338 had some significance, and the reason seems to have been lost to time.

Of course, as a scientist, ‘lost to time’ is not a satisfactory answer; 338 had to mean something. Someone a long time ago had gone through the process of putting gold leaf on this piece of wood, and could have spent less time just placing it in strips or patches, and the result of the experiment would have been the same. I needed to know what 338 could mean.

Searching for the meaning of 338

I began my search for a link between Tyndall and the number 338 with my colleague Hope, and together we exhausted some avenues of speculation. It didn’t seem to relate to any important dates in Tyndall’s life - nothing of note happened in March 1938, Tyndall would have been about 17 years old and seemed to still be in education. It wasn’t easy to locate Tyndall’s address at the time, so we didn’t think it was the sign for his house number, and although Tyndall grew up in a religious environment, it was very unlikely to be a bible verse number as he was famously agnostic. Trying to figure out if it was a significant number in terms of mathematics was too difficult for us to begin to think about (neither of us being mathematicians), although since Tyndall had had an education that included English, logic, bookkeeping, drawing, surveying, and associated mathematics, it could easily have been a complex mathematical formula. We decided we would circle back to that possibility if we couldn’t find a simpler answer.

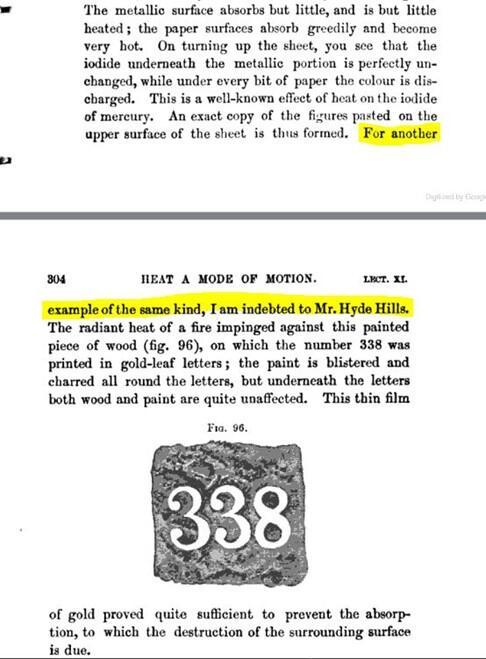

My breakthrough came when referring once more to Heat. A mode of motion. There was a mention of a name on the page which featured the illustration of our burnt piece of wood; ‘For another example of the same kind, I am indebted to Mr Hyde Hills.'

The sentence doesn’t provide much context as to who Mr Hyde Hills was, or why Tyndall was indebted to him, but it was the only lead I had. Fortunately, we live in an age where information is so easily accessible. I decided to simply Google ‘Hyde Hills 338’ and see whether anything would come up. And to my surprise, something did.

Who was Thomas Hyde Hills?

Thomas Hyde Hills was the president of the Pharmaceutical Society from 1873-1876, and the proprietor of the John Bell and Co. Pharmacy which had an address of 338 Oxford Street in 1849. Could this be the Mr Hyde Hills that Tyndall was indebted to?

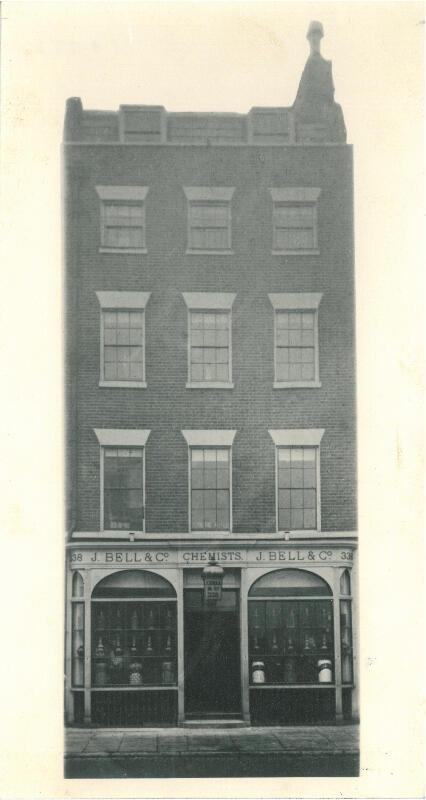

I wondered if the piece of wood with 338 printed on it was in fact a shop sign from the pharmacy donated by Hyde Hills. This led me to trying to find paintings or photographs of the pharmacy at 338 Oxford Street. At first all I could find was an engraving of an apothecary and his apprentice working in the laboratory of John Bell’s pharmacy as it was in 1841 (just before Hyde Hills became the owner).

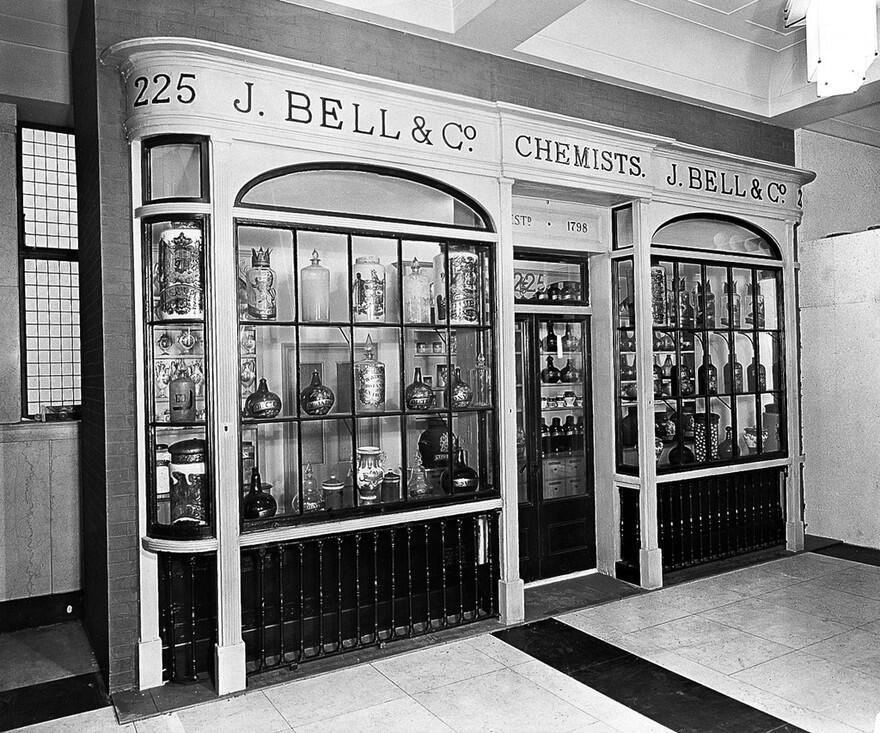

However, I was excited to discover that the Wellcome Collection has a reconstruction of the John Bell and Co. Pharmacy store front on display in their main hall. I was hoping it would be the 338 Oxford Street shop front with a wooden and gold sign just like the burnt one in our collection.

But my excitement was short-lived. The shop front in the Wellcome Collection is from a later period in the Pharmacy’s history when the it was renumbered from 338 to 225.

The Pharmaceutical connection

I had one last avenue to explore, which was to try and find a photograph of the pharmacy when it was at 338 Oxford Street. I decided to contact the Pharmaceutical Society directly to see if they had any information about Thomas Hyde Hills, his relationship with John Tyndall, or even any images from the Pharmacy at 338 Oxford Street. I was in luck.

The Pharmaceutical Society, now called the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, was founded by Jacob Bell; John Bell’s son, and they had the information I was looking for. Their Museum Manager was quick to get back to me with a stunning photograph of the shop front at 338 Oxford Street, and an even more impressive photograph of the inside of the pharmacy, where it appears as though Mr Hyde Hills himself is in the background. Take a look at the man leaning against the table and compare him to the Millais portrait of Hyde Hills.

I had the photo I had been looking for, but there was no wooden 338 sign to be seen. Perhaps it was older than the photograph and had already been taken down, or maybe it featured inside the pharmacy and wasn’t ever photographed. Sadly, the building at 338, later 225, Oxford Street was demolished in the 1980’s.

The mystery continues

I regret to say that this story does not have a conclusive ending. While it appears to me that the sign must have come from the Pharmacy in some way, taking into account that Tyndall was indebted to Mr Hyde Hills for something, and that Hyde Hills had resided at 338 Oxford Street at the time, without concrete evidence we can only speculate. Perhaps Hyde Hills had made it specifically for Tyndall but saw an opportunity to promote the Pharmacy; perhaps he gave Tyndall the gold leaf and Tyndall decided to arrange it as 338 to acknowledge Hyde Hills’ gift; perhaps 338 is in fact the answer to some form of complex logic puzzle that Tyndall devised.

The Ri collection of objects

Wherever the 338 sign came from, it is one of the rarest items in our collection, or indeed any museum’s collection, and that is because it is the result of a successful experiment. Lots of collections have experimental apparatus and the associated archive, but few have been able to keep the results of experiments. This fragile piece of wood with gold 338 numbers is special, and has helped to illustrate Tyndall’s scientific principle, as well as capture a demonstration.

Although our 338 experiment result is too fragile to be on permanent display, it is sometimes taken out of its wrapping (very carefully!) for talks and demonstrations. Our collection is full of interesting scientific and historical artefacts which are on display throughout the publicly accessible floors of the building. I would urge all of our Members to stop by and visit, and see if you can discover any more mysteries of the Royal Institution.