In this very important year for the Ri, marking 200 years of the CHRISTMAS LECTURES, 200 years of Discourses and 200 years since the discovery of Benzene, we are taking the opportunity to look further into the man from our past that links them all, Michael Faraday.

Faraday is everywhere at the Ri. His collection of scientific apparatus makes up a large part of the historical collections the Ri holds. His image can be seen throughout our spaces, in photographs, paintings and sculptures and some even say they can feel his presence when they take to the stage of our iconic lecture Theatre, a place Faraday called home and through his lectures cemented it as an iconic place to communicate science.

Almost since Faraday’s death, the Ri’s archival holdings related to the works of this great man have been a place of pilgrimage resulting in hundreds, if not thousands of articles and books detailing his scientific research and developments. The core of this collection are the 10 scientific notebooks which hold all his scientific experiments and development of ideas, including the electric motor, induction ring and generator amongst many others. These 10 notebooks have been widely consulted and analysed and found to hold such fundamental scientific research that we had the privilege, in 2016, of having them submitted to the UK Register for the UNESCO Memory of the World Archive.

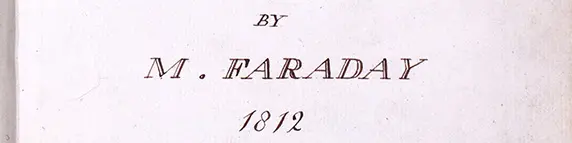

However, there is still material which is less known. Not quite hidden within the Faraday collection, there is a box containing five small notebooks. These little gems were created by Michael Faraday between 1810 and 1812, and contain not his research, but his understanding of other people’s scientific discoveries and teachings. These help to illustrate a young Faraday’s passion for knowledge and understanding, and his early connection with the Ri.

Michael Faraday, born in 1791, came from a modest family. He was the son of a Blacksmith and was brought up in Newington Butts or Elephant and Castle as it is better known today. Coming from his social economic background, Faraday attended a ‘common day-school’, describing in later life that his ‘education was of the most ordinary description, consisting of little more than the rudiments of reading, writing and arithmetic’. When he was 13, Faraday was employed first as a newspaper and errand boy by George Riebau and then soon rose to become an apprentice bookbinder. It was during this time that he gained a passion for science, often reading the books he bound but also attending, when he could, lectures and demonstrations held in public institutions, and private drawing rooms.

In 1810, Faraday began to attend Silversmith John Tatum’s series of lectures given from his home near Blackfriars's Bridge. These lectures were open to men and women on the payment of one shilling per lecture. Faraday attended 13 lectures in total from February 1810 to September 1811. We know primarily about his experience of attending through the four beautiful bound notebooks he produced for his own record. These notebooks contain his studious write ups of lectures on topics of geology, minerology, galvanism, optics, combustion, hydrostatics, mechanics and electricity. Faraday not only painstakingly took detailed notes in the lectures but on binding the material together completed each book with detailed illustrations and thoroughly indexed the content. In each book he conveys the theory and describes in detail the practical demonstration and the equipment used.

It was the creation of these four notebooks which, when shown to Riebau and a Patron of the shop in early 1812, led to him attending the last four lectures to be delivered by Humphry Davy, Professor of Chemistry, at the Ri. Faraday carried on his book writing skills, producing a book of notes on Davy’s lectures. This beautiful volume is the fifth book in our set and is ultimately the tool he used to get to not only meet Humphry Davy but within several months be employed at the Ri and set him on his path of scientific discovery and communication.

The rest, as they say, is history.

These notebooks hold a special place within the rich archive of Michael Faraday. With ongoing internal digitisation - including through a fully searchable heritage collections database - it is hoped that they will eventually be available online for audiences to enjoy freely. But in the meantime, they deserve to be highlighted. They help demonstrate the process that we all do today, whether in school or in work, taking notes and making drawings in our own words to understand something new. You never know where this process may take you and I wonder if Faraday, when first sitting in the Ri’s lecture theatre in 1812 as a 20-year-old bookbinder, ever dreamed he would become one of the most famous scientists of his time and that his inventions would continue to shape the modern world nearly 160 years after his death, touching our lives, every day.

These 5 notebooks will be on display for a period of time within the Ri’s free Michael Faraday Museum, 21 Albemarle Street, London from 14th April.