It’s unlikely that you haven’t heard of the plastic problem. The banning of plastic straws and the removal of single-use plastic bags are just some examples of changes we have seen implemented over the last couple of years. But how impactful are these changes? How can we reduce our plastic footprint? And what are the latest innovations in science that are likely to have a real impact?

Back in 2019, the UK government confirmed a ban on plastic straws, drink stirrers, and plastic cotton buds in England which took impact from October 2020. Exemptions are to be made for those who need to use plastic straws for medical reasons or because they have a disability. They will be able to purchase them from pharmacies and make requests in restaurants and bars.

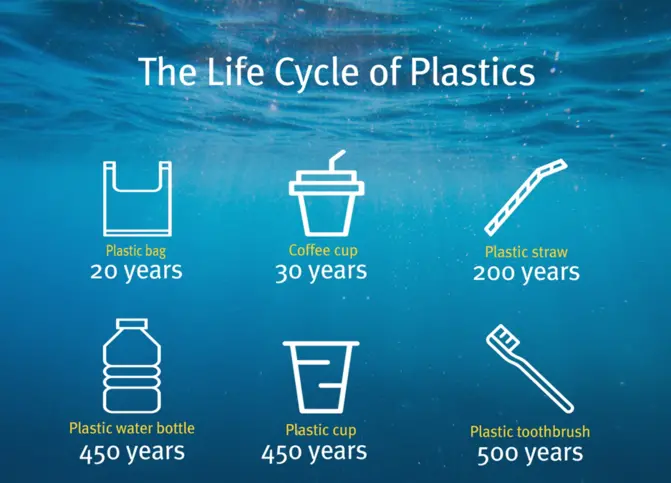

It’s estimated that the UK uses 8.5 billion plastic straws every year. Most straws are made from plastics called polystyrene and polypropylene which, if not recycled, take hundreds of years to decompose. Plastic straws are frequently reported to rank among the top ten items found in beach clean ups.

So, the government’s decision on their ban is a good thing – right?

Well yes – but – it is not single handily going to solve the plastic problem. Emma Priestland, campaigner at Friends of the Earth, is concerned that these actions will only have a limited impact.

“Legislation to cut down on pointless plastic is good to see but these three items are just a fraction of the single-use plastic nasties that are used for a tiny amount of time before potentially polluting the natural environment for centuries to come,” she said.

“Ultimately, we need producers to take responsibility for the plastic pollution caused by all their products, whether it’s bags, balloons, packets, containers or otherwise. That’s why we’re campaigning for legislation to cut back on pointless plastic across the board.”

However, this is not to say that we should just leave it up to government. There are PLENTY of changes that you can make that will have a positive effect on our environment. Our friends at National Geographic have listed some suggestions.

Innovations in science and technology

So, what are some of the scientific and technological solutions that may help reverse the devasting effects of plastic? We take a look at just a few below.

The Ocean Cleanup

A 24-year-old entrepreneur, Boyan Slat, launched The Ocean Cleanup project nine years ago. Boyan’s organisation aims to clean up the Great Pacific garbage patch, which floats between Hawaii and California and is reported to be more than twice the size of Texas.

The Ocean Cleanup has designed a technology which is effectively a large floating scoop. It consists of a 600-metre-long floater which sits on the surface of the ocean and is tapered down with a 3-metre-deep skirt attached below. It is a passive system, using the natural forces of the ocean to catch and concentrate the plastic. The system and plastic are carried by the ocean’s current.

System 001 was launched from California in September 2018, however there were problems with retaining plastic in the system, it then broke apart the following year and was brought in for upgrades and repairs. In a recent blog update, Boyan says all but one of the known issues with System 001 have been resolved. The last obstacle to overcome is called ‘overtopping’, where plastic overtops a screen which is meant to retain it. Boyan says the cleanup crew has recently finished production of a new screen which he is confident will solve the problem.

Plastic eating bacteria

Another major breakthrough for scientists was the discovery of a bacteria that can digest plastic. In 2016, scientists from Japan tested different bacteria living on plastic bottles in a recycling plant and they found thatIdeonella sakaiensis 201-F6 could digest polyethylene terephthalate, a plastic used to make single use drink bottles.

The bacteria work by secreting an enzyme (a specific type of protein which can speed up chemical reactions) called PETase. This splits certain chemical bonds (esters) in PET, leaving smaller molecules that the bacteria can absorb, using the carbon in them as a food source.

Emily Flashman, Research Fellow in Enzymology at the University of Oxford, notes the improvements to the PETase activity were not substantial, and we are a long way off in finding a solution to the plastic problem. Nevertheless, Emily highlights how this research helps us understand how this capable enzyme breaks down PET and suggests how we could make it work faster by manipulating its active parts.

Tiny magnetic coils to help break down microplastics

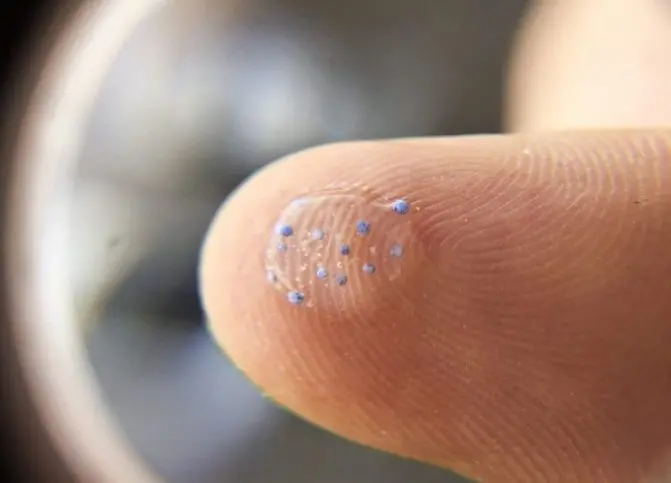

More recently, researchers at Adelaide and Curtin University in Australia have invented tiny magnetic coils, half the width of a human hair, which could help rid microplastics from our oceans.

It’s not just the plastic you can see which is polluting our oceans. Microplastics, defined as less than 5mm in size, have been found in 114 types of aquatic life, over half of which are consumed by humans.

The coils under the microscope look like bedsprings. Each is coated in nitrogen and a magnetic metal called manganese. When together, they react to create oxygen molecules that attack plastic and help break it down.

The team of researchers added the coils to water samples contaminated with microplastics. They tested the water eight hours later and identified a 30 to 50% reduction in microplastics.

This blog was first published in August 2019 but has been updated in November 2022.