Though humans have been looking up at the sky since the dawn of our species, we never really had the technology to study the details of celestial phenomena like eclipses. That is, until the telescope and the camera were around, and Warren de la Rue got his hands on both.

Let’s look at what records tell us about this pivotal moment in the history of astronomy, and jump back to modern times to see what we know today about eclipses.

The history – with Charlotte New, Head of Heritage and Collections at the Ri

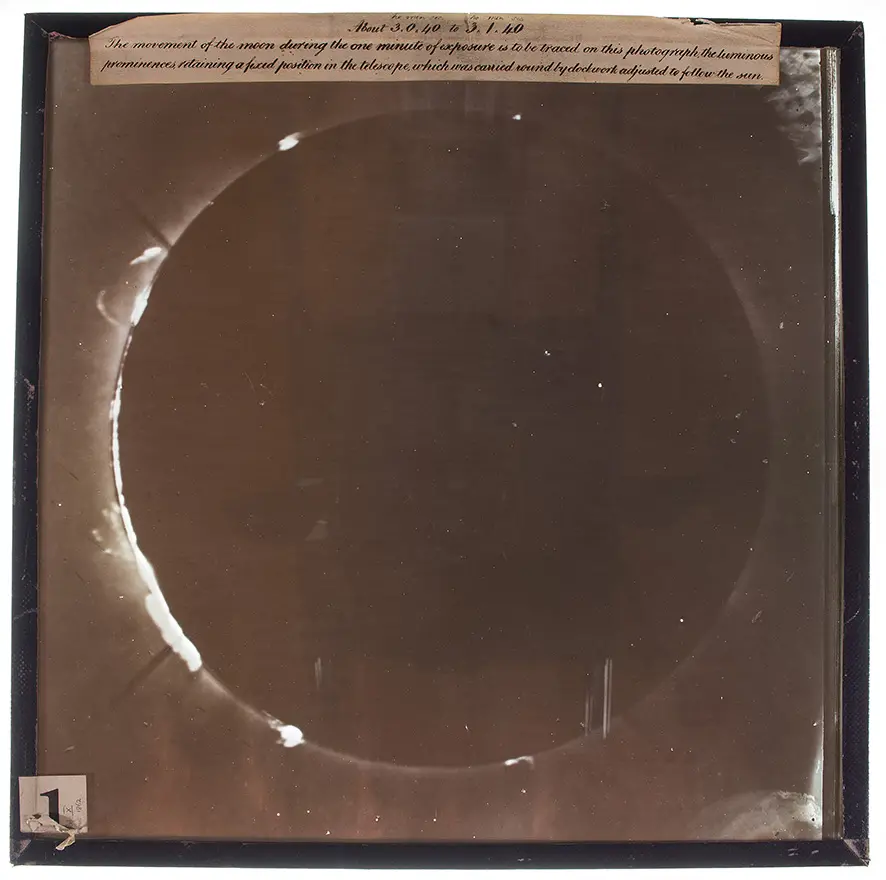

There’s a reason Warren de la Rue is often referred to as “the father of celestial photography”. He took some of the most stunning, detailed photos of celestial objects of his time, and invented many instruments for astrophotography. He was also the person who discovered a key aspect of the nature of solar eclipses, and proved it by getting it on camera in what is likely the first instance of an astronomical debate being settled by a photograph.

The cause of this debate was found in solar eclipses. Astronomers in the mid-1800s observed mysterious flames dancing around the edges of these eclipses, but nobody could figure out exactly what they were made of and where they came from — were they an optical illusion, or a phenomenon coming from the moon or even the sun?

In July 1860, de la Rue and his crew set sail for northern Spain in what would be the very first expedition with the aim to photograph a solar eclipse (there are many companies offering this as a service that you can book online these days). They, of course, packed their photoheliograph, a telescope-camera hybrid that de la Rue designed specifically to photograph the sun.

On 18 July 1860, the team took 40 photographs of the most important solar eclipse of the 19th century, including two shots in total eclipse. This was an extremely difficult task, as the exposure time for a photograph in low light conditions would’ve been around one minute.

And there they were, the controversial tentacles of light. De la Rue said the photos:

'depicted the luminous prominences with a precision as to contour and position impossible of attainment by eye observations'.

The question still stood. Was this a phenomenon coming from the Earth, the moon or the sun? The solution was found, like it often is in science, by comparing notes with other researchers. Had the mysterious flames been caused by the Earth or the moon, they would have appeared differently in photographs from other parts of the world. But they didn’t — they matched perfectly with photos from other astronomers, thus confirming that they were solar in origin.

A few months after the astronomical community was shaken by this photograph, Michael Faraday delivered a Friday Evening Discourse at the Royal Institution "On Mr. Warren de la Rue's Photographic Eclipse Results". De la Rue's association with the Ri predated his eclipse expedition, and continued long after that, as he became Ri Manager and lectured here frequently.

One of his most relevant lectures might surprise you: it was titled "The History and Manufacture of Playing Cards" (1837). De la Rue's family, originally from Guernsey, had a printing business which went on to become one of the largest in the world. Today, they print all of the UK's banknotes, and one third of the world's banknotes have security features designed by the de la Rue printing company.

The science of eclipses – with astronomer Affelia Wibisono

A solar eclipse is a great reminder of the celestial dance the sun, Earth and moon have practiced for the past 4.5 billion years or so. Our planet orbits the sun once every 365.25 days while the moon completes a lap around the Earth every 27.3 days. Our satellite finds itself in between us and our star every month, however, its tilted path around the Earth means that the three only align in the same plane roughly once every 18 months. This means we get a solar eclipse somewhere on the Earth every year and a half as the moon casts its shadow on our planet.

Those who find themselves in the moon’s inner shadow (the umbra) are treated to a total solar eclipse as the sun hides behind the moon. Typically, the moon’s umbra is between 150-250 km wide (the actual size depends on the latitude on Earth and the distance between the Earth and the moon at the time) which is why on average total solar eclipses occur every 375 years over a particular location on Earth! To see how long you need to wait for the next solar eclipse (or any eclipse!) to happen in your hometown, go to timeanddate.com/eclipse

Other planets with moons can also have solar eclipses. In fact they happen almost daily on Mars and several rovers on the red planet have taken photos and videos of these eclipses since 2004. However, total solar eclipses are rare across the Solar System. We only get to enjoy them due to a fortunate coincidence – the sun’s diameter is roughly 400 times wider than the moon’s, but it’s also about 400 times further away from us which gives the two the same apparent size in our sky.

There are times when the moon appears to be too small to completely obscure the sun during a solar eclipse because of its slightly elliptical orbit and varying distance to the Earth. This type of solar eclipse is called an annular eclipse and the moon looks to be surrounded by a ring of light. Our moon is also receding by about 3.78 cm every year which means that in the future every solar eclipse on Earth will be annular – so make sure you do all you can to catch a total solar eclipse while you still can! You’ve only got a few hundreds of millions of years left.

Anyone under the moon’s outer shadow (the penumbra) will experience a partial solar eclipse where the moon appears to take a bite out of the sun. Everyone else in the world unfortunately will not see the eclipse at all.

To view an eclipse safely, it's vital to never look directly at, or at a reflection of, the sun. This includes during a solar eclipse. It can be very tempting to look at a total solar eclipse with the naked eye, but even catching sight of the smallest sliver of the sun can be damaging. Totality (when the sun is completely blocked by the moon) usually only happens for a minute or two, and it can be difficult to know exactly when totality starts and ends. Therefore, it’s safest to wear eclipse glasses (NOT regular sunglasses) or to project an image of the sun using a pinhole projector if you want to see another solar eclipse.

About the authors

Charlotte New is Head of Heritage and Collections at the Royal Institution. Read her latest article on JJ Thomson and the discovery of the electron

Affelia Wibisono is a PhD Student at the Deptartment of Space and Climate Physics at UCL, and a former Christmas Lectures Intern at the Ri. Find out more about their work