"The noblest figure for us was a soldier in full kit covered in the sacred mud of Flanders, or the Somme. But on the other side of the line the scenic artist had raised, like a canopy, acres of picturesque landscape."

Strange words from Solomon J. Solomon (1860–1927) in 1921, a London portrait artist who made a living in World War 1 painting posthumous portraits of husbands and sons who had been killed in action. He is not perhaps the first person one might expect to have given a Discourse at the Royal Institution (from the abstract of which these words were taken) but he was also an expert in camouflage.

Solomon first attracted military attention by his letter to The Times of 27th January 1915. A few sentences will serve to convey its flavour.

"Sir — The protection afforded animate creatures by Nature’s gift of colour assimilation to their environment might provide a lesson to those who equip an army; seeing that invisibility is an essential in modern strategy…

‘The artillery officer is covering his gun with grey tarpaulin, but with a team of six or eight horses in front of it, the airman is not likely to mistake it for a butcher’s cart. The horses have merely to be covered with a thin grey-green stuff to make them equally inconspicuous. Wagons are a leaden grey, unlike anything in nature; a warm dust colour would be more harmonious…

‘The great thing, next to protective colouring, is breaking up the outline…"

After his letter appeared he was sent off to visit French camoufleurs (also artists) in the Pas de Calais and then asked to help set up a military ‘Special Works Park’ in Kensington Gardens, a short stroll from his home. That was the cover name for a place to teach the art of camouflage. In the patch of ground between the Long Water and the West Carriage Drive trenches were dug. Dugouts, guns, hangars and gas emplacements could be experimentally draped with various coverings in benign surroundings with a view to concealing the same along the front line.

Being a London geek, when I first heard about Solomon, I walked across this grass and studied Google Earth images to see if any outline remained, but there were none. Recently I came across the Discourse Solomon gave on the subject of camouflage in 1921 and it renewed my interest. But here was an odd thing. His Discourse was not about British camouflage. I was surprised to find that it focused on the German efforts.

I also tried the British Library for more detail about his life and the Special Works Park. I did not find what I hoped for, but I found a more exciting story, also about camouflage, and suddenly I understood the context of Solomon’s 1921 Discourse. In 2014 it is not unknown for an Ri lecturer to discourse on the subject of a forthcoming book, and so it was in 1921. Solomon had a book coming out: Strategic Camouflage, his revelation of a breath taking wartime secret as its subject.

In 1918 he came to view his own puny efforts in the context of, he believed, a colossal German triumph of deception. As Solomon saw it, his own successes in concealing a gun here or an observation post there were merely tacticaldeceptions, designed to protect individual targets from being shelled. The Germans, he argued practiced strategic deception. That is, they had successfully concealed a massive build-up of men and material. He wanted to warn the nation before it was surprised by this technique in the next war.

In World War 2 photographic intelligence was a decisive asset available to the Allies, of much the same importance as Bletchley Park. For example, it gave vital information about the V1 and V2 secret weapons. But photography also played a part in World War 1. Solomon remarks that the ‘extraordinary capacity’ of the camera was not appreciated until a camera was salvaged from a wrecked German plane and the film was developed. Observers and even pigeons were sent aloft with cameras. Solomon came into possession of some photographs of St Pierre Capelle and Sparappehoek taken by his cousin from a kite balloon. He had just bought a magic lantern projector, but found it disappointing. But what he did with his new bright light was to examine in minute detail the photographs he had been given. What he saw was that the shadows were wrong, that fields looked odd for the time of year, and that the landscape had inconsistencies and imperfections as if it was an imperfectly executed sketch.

As an artist, he understood how colour and shade can detach a feature in a flat painting from its background. In a war, your shadow could kill you. When draping nets over an object it was important to soften the angles. The nets should not just be pegged around the base of the object, they should slope gently away.

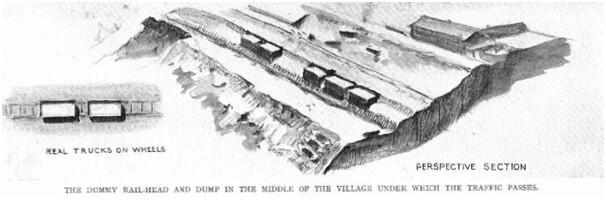

He was told that no traffic had ever been observed on the road from St Pierre Capelle to Nieuport despite it being the only road to the front from Bruges. Of course movements at night would go undetected, but with his analysis and the erratic shadows of the trees it was clear that lengths of road had been covered with painted nets to conceal day time activity. The more he looked the more he saw that the entire landscape was an elaborate hoax. Real railways were covered and decoy lines were painted. A few trucks were scattered in sidings, but these were just theatrical props on top of a busy railhead. He saw that large farm houses cast no shadows. It meant that huge canopies of netting and tarred paper had been raised to the level of the eaves and that the farm house was perhaps surrounded by a mass of invisible infantry and weapons. All that was visible was a row of haystacks in a field, the shadows, staying fixed as the sun traced its arc. In short, the Germans had been able to hide a whole army ahead of a major advance, Ludendorff’s spring offensive of 1918.

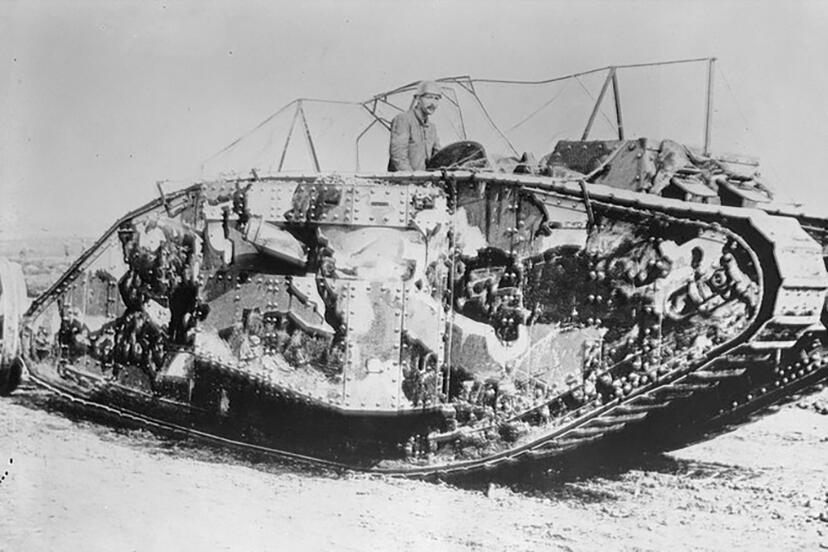

If we look now at his book, the black and white photos are grainy, the diagrams fuzzy and his captions are frustratingly terse and ambiguous. It has not been easy to select useful illustrations for this blog. Was Solomon deluded? He was not generally believed. ‘Alas, I was powerless — and could only wring my hands!’ he wrote.

The Spring Offensive was real enough and involved a surprise attack by hundreds of thousands of German troops withdrawn from the Russian Front. It is a cliché of war that history is afterwards written by the victors. So it is that we do not hear at length of a German triumph of strategic deception. But Solomon received anecdotal evidence of net canopies being found intact after a German retreat, and some German writings gave them mention. So, perhaps he was right.

About the author

Laurence Scales leads London tours featuring the history of science, invention and medicine. He is a graduate in engineering who has worked in various technological industries. He can be found on Twitter as @LWalksLondon