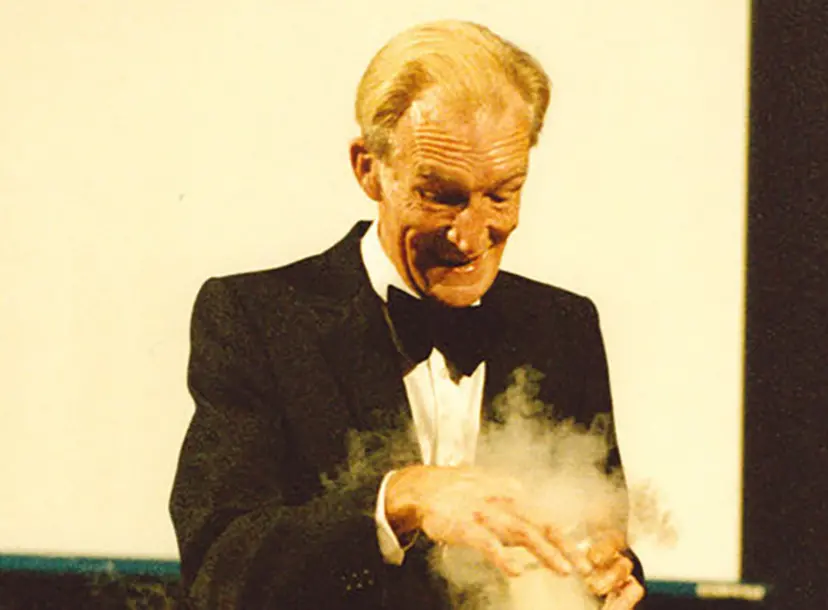

It is impossible to discuss the CHRISTMAS LECTURES without conjuring the image of Bill Coates—a towering, sharp-witted figure whose inventive demonstrations brought complex science to life. Between 1948 and 1986, Bill was the indispensable assistant to countless lectures, the face behind the ingenuity that turned abstract theories into unforgettable spectacles. He was the Ri’s very own master of demonstration. Yet, this role was just one facet of a remarkable career that spanned battlefield bravery, important laboratory work, and a legacy of science education that extended far beyond the Royal Institution.

How did a boy from London’s East End become one of the most recognizable figures in televised science, a trusted collaborator to Nobel Prize winners, and even a lecturer at the Ri in his own right?

From the East End to the Ri

On 7th November 1919, William Albert Coates was born in the East End of London. After attending Shoreditch grammar school, in 1934 he began as an apprentice at the Exchange Telegraph Company. In the evenings, he attended physics and engineering classes at local London Polytechnics. Like many of his era, Bill also spent time in the Army. He was a Private in the London rifle regiment of the Territorial Army when war broke out in September 1939. Bill would often recount stories of his time in the Army; he volunteered to be part of the Parachute Regiment when it was formed in 1941 and was a part of the D-Day operations in June 1944. Dispatches even recounted how he jumped from a burning aircraft during the crossing of the Rhine in 1945. When he was demobilized in Autumn 1946, Bill had achieved the rank of Captain.

After the war, Coates had applied to join the police force but was rejected (to his own disbelief) due to the state of his teeth. His prior training at the Exchange Telegraph Company gave him the skills to work as a fitter for Mullard Engineering, but he did not stay there for long. In 1947 he joined Charing Cross Hospital medical school as a technician. Only a year later, Bill was appointed as a laboratory assistant in the Davy-Faraday Laboratory at the Ri, and it was here that he would spend the rest of his working life.

X-Rays and Demos: Life at the Ri

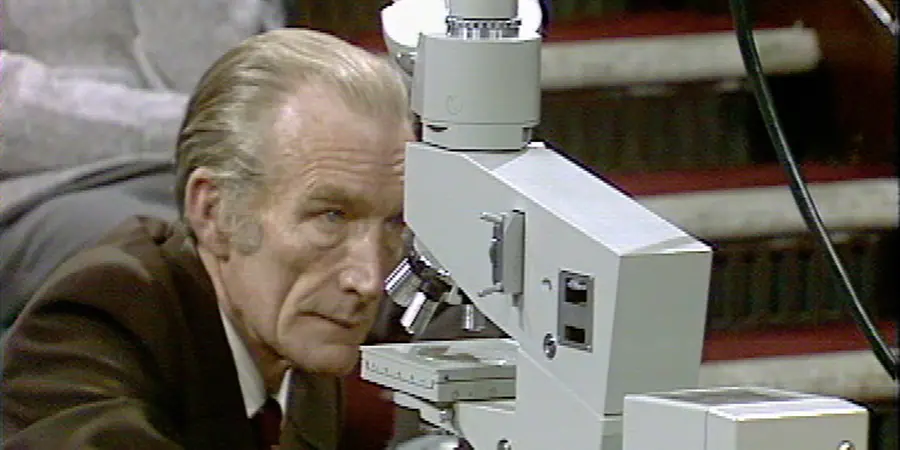

When Bill joined the Ri under Director Eric Rideal, he became part of a world-leading centre for X-ray crystallography studies; automatic single-crystal diffractometers and rotating anode X-ray tubes were all made in-house in the workshop, before being put to work in the nearby laboratories. Working under Uli Arndt and David Phillips, Coates showed incredible aptitude across a broad range of laboratory skills.

Then Professor of Metal Physics, Ronald King, suggested to Bill that he might be suited to helping with lecture demonstrations. Scientific demonstrations were a hallmark of the Ri’s public engagement with science, a tradition going back to the years of Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday; lecture audiences did not just expect to hear about scientific advances, but to see them. A real turning point occurred when William Lawrence Bragg arrived as Director of the Ri in 1953. Bill recalled:

“One afternoon in the early 1950s I was repairing an X-ray target in the workshop at the Royal Institution when I suddenly became aware of our new Director standing beside me. After a friendly greeting and an inquiry as to what I was doing, he asked me if I knew that rubber contracted when heated. Rather taken aback by the question, I replied that I did, but had no idea why. He immediately gave me an explanation as to why this happened, and then inquired of the possibility of producing a model to demonstrate this action.”

From this point on, Bill helped illustrate scientific phenomenon for both the CHRISTMAS LECTURES and the Friday Evening Discourses, with the latter often within a particularly short time frame of only a few days. His ingenuity is centre stage of Terence Cuneo’s famous depiction of Bragg’s 1961 CHRISTMAS LECTURES; as seen in the centre of the painting, Coates repurposed two toilet cistern float balls to neatly demonstrate the laws of electrostatic repulsion. This perhaps unusual yet strikingly effective apparatus is still on display just outside the Ri Theatre today.

On occasion, Bill himself became the subject of the demonstration. One particularly memorable demonstration involved the ‘radio pill’, a pressure-sensitive capsule containing a radio transmitter that emitted a small noise when pressed. As Bragg later recounted in his letter to a future Christmas Lecturer, Heinz Wolff:

“The radio pill was an uproarious success… the children were able to punch him during and after the lecture and hear the squeaks.”

Watch Bill assisting Lawrence Bragg in a 1962 lecture

Bill’s collaborations continued with Bragg’s successor, George Porter, as well as the other Directors and international scientists during the mid-to-late-twentieth century. In recognition of his contributions and skills, The Clothworker’s Company provided funds to establish the post of Clothworkers’ Lecturer and Lectures Superintendent, of which Bill became the first occupant. He was awarded the Bragg Medal from the Institute of Physics in 1975 for his significant impact on the education of physics, and was awarded an MBE in 1980.

Though nearly always the assistant, Bill was given the honour of giving his own Friday Evening Discourse near the end of his career. Reversing their roles, on the 9th of November 1984, George Porter took on the role of aiding Coates with his favourite demonstrations from the past 40 years, and some would perhaps note that Porter was perhaps not quite as deft as Bill. Bill retired from the Ri two years later.

Retirement and legacy

Even in retirement, however, he barely slowed down, continuing to demonstrate science both in and outside of the Ri. He was involved in the production of several foundation courses at the Open University, notably on the elements of the Periodic Table and on photochemistry and solar energy, both topics with histories close to that of the Ri. The Schools Liaison team at Imperial College benefited from his advice too, while he also found a niche as a consultant for the BBC, contributing to many of their science programmes, including Take Nobody's Word for It, a DIY science show with Carol Volderman and Professor Ian Fells.

During this period Bill’s health began to decline, in part a result of his smoking habits. After battling lung cancer for over a decade, following a pneumonia infection, he died on the 7th October 1993 in Kingston Hospital, London.

Today, Bill's legacy is apparent for all to see, most recently in the 2024 CHRISTMAS LECTURES with Chris van Tulleken. The ‘tiny’ frying pan demonstration dreamt up by the Ri’s Head of Demos, Dan Plane (a direct professional heir of Bill Coates) had all the hallmarks of classic Coates – humour, drama, fire, and above all, an accessible explanation of science.

Bill has sometimes been referred to as a shrewd technician, or jack of all trades, even a human guinea pig at the whim of various lecturers. But what is most clear is that during his long and esteemed career, Bill embodied the single most prominent technique at the heart of the Ri’s mission to bring the public and scientists together: never to just tell people about science but show it to them.

#Discover200 years of science

2025 will be a year of celebrations at the Ri, as we mark the 200th anniversary of the momentous year in which Michael Faraday discovered the chemical benzene and founded the CHRISTMAS LECTURES, as well as the Discourses lectures series, both still taking place today.

Stay with us as we explore the past, present and future of science.

About the author

Dr Katy Duncan is a historian and occasional philosopher of science and the current Postdoctoral Freer Fellow at the Royal Institution.

Katy is interested in how scientific instruments work, from their making to their breaking, and what this tells us about the scientific process. She specialises in atmospheric-electric phenomena and related disciplines, and is interested in the physical sciences broadly construed from the 19th century onwards.